16 February 2024

Cathedral Church of the Holy Communion, 17405 Muirfield Drive, Dallas, Texas

OT reading (Isaiah 61); Psalm 23; Epistle (1 Timothy 3); Gospel (John 21)

Gradual Hymn #220 (1940) “God of the prophets, bless the prophets’ sons”

The opening words of our Epistle, I Timothy 3:1 – ‘If a man desire the office of a bishop, he desires a noble work.’

‘This is the episcopacy to which we adhere,’ cried George David Cummins at the conclusion of his sermon at the episcopal ordination of Charles Cheney, ‘the episcopacy of Polycarp and Ignatius … found existing almost universally in the churches of the second century, an episcopacy which is a bond and centre of unity [and] admirably fitted to promote the well-being of the whole visible Church of Christ’.

Bishop Cummins spoke those words just over 150 years ago, on 14th December 1873. Since then, by my reckoning, sixty-four bishops have been consecrated in the Reformed Episcopal family. You, John, will be the sixty-fifth.

And down that century and a half echo Bishop Cummins’ vision and challenge: ‘This is the episcopacy to which we adhere … the episcopacy of Polycarp and Ignatius’.

So who were these men that we Reformed Episcopal bishops are to emulate? What is the pattern of episcopacy that they hold up before us?

Ignatius was bishop of Antioch in Syria (modern Antakya in Turkey). He appears to have become bishop in about AD 69 following the death of his predecessor Euodius, who, according to Eusebius, was the first to hold that office after St Peter. After a long ministry, in the early second century Ignatius was arrested and taken to Rome. The Colisseum was newly built and it seems it was for such an efficient killing arena that there weren’t enough local victims and prisoners from around the Empire were to be sent there to die. During his journey to Rome Ignatius wrote a number of letters which survive. He probably died in either 108 or 115AD.

Polycarp was bishop of Smyrna in Asia Minor (modern Izmir in Turkey). He was probably born about AD 70 and lived at least until his 80s and was martyred in the year 155AD. He was bishop of the church in Smyrna for about 50 years. Smyrna is of course one of the seven Churches of the Apocalypse and seems to have had its struggles: ‘I know your tribulation and your poverty (but you are rich) and the slander of those who say that they are Jews and are not, but are a synagogue of Satan’ (Revelation 2:9). By the time of his death Polycarp seems to have overcome these challenges and was loved for his gentle wisdom and holiness.

Ignatius and Polycarp knew each other – they corresponded. So what are we to learn from them about the episcopal ministry? What lessons do they teach us – and you in particular, John?

- Sit at the feet of the Apostles.

Irenaeus tells us ‘Polycarp was not only instructed by apostles, and conversed with many who had seen Christ, but was also, by apostles in Asia, appointed bishop of the Church in Smyrna’.

Polycarp was instructed by Apostles. That, John, must be the foundation of your ministry as well – to be instructed by the Apostles. As Acts 2 tells us, adherence to the Apostle’s teaching was a hallmark of the earliest Christian communities and it must be the hallmark of your ministry. It is your duty to guard the deposit of faith you receive from the Apostles, to live by it, to call others to embrace it, and to pass it on unsullied to your successors.

And that’s not just a matter of handing on facts. As John Stott has said,

‘It is extremely important to recover today an understanding of the unique authority of Christ’s apostles. We have put our trust in Christ, and we have done it through the apostles’ teaching. If the apostles had not borne their unique testimony to Jesus Christ and if their unique first-hand testimony had not been preserved and recorded in the New Testament, we could never have believed in Jesus.[1]

It is the apostolic writings of the New Testament that show us what the Lord Jesus achieved on the Cross; and what men, women and children must do to be saved – so they equip us for evangelism, for bringing others to a life-changing encounter with the Lord Jesus Christ.

To gain both understanding of the Gospel and motivation for his ministry, a Reformed Episcopal bishop must sit at the feet of the Apostles.

- Stand up against false teaching

Being faithful to the Apostles’ teaching requires not simply the positive and fulfilling ministry of proclaiming the Gospel and forming disciples, but also the necessary task of refuting error. This is a recurring theme in the writings of Ignatius and Polycarp. In their day the main presenting issues were a judaising tendency and a denial that Jesus had truly come in the flesh – a denial of the reality of the incarnation. In our own day we have different presenting issues that threaten to lead people astray. Some are external – attitudes in society that challenge the very premises of Christian truth. Others are internal – arguments within the Christian body itself. I am not going to be more specific, not least because I am aware that the process of discernment is currently painful over here.

Later in this service, you will be asked, ‘Are you ready, with all faithful diligence, to banish and drive away from the Church all erroneous and strange doctrine contrary to God’s Word; and both privately and openly to call upon and encourage others to the same?’ That’s an important part of your mandate, John – not always the easiest part. To stand up against false teaching. But it’s a duty that you will share with Ignatius and Polycarp.

- Be a centre of unity.

Bishop Cummins, as we all know, had grave concerns about exaggerated claims for the ministry of bishop. But, rightly used, he believed one of its greatest strengths was that it could serve the unity of the Church, a cause in which Cummins passionately believed. Of Ignatius he writes: ‘to him the value of episcopacy is that it is a visible centre of unity’. He quotes Ignatius writing to the bishop of Smyrna: ‘Have a care of unity, of which nothing is better’; ‘Let nothing be done without your consent, and do nothing without the consent of God’.

The dynamic witnessed to by Ignatius is of the bishop at the heart of the Christian community gathered around him and holding it together. This is not just organisational – it is sacramental. The only Eucharists recognised as valid are those presided over by the bishop or someone appointed by him. There is a mystical connection between bishop and people, made visible in the sharing the One Bread.

But the bishop is not alone at the centre. Over the years, John, the men whom you will ordain (and they will of course be men) will form a team of deacons and presbyters to share with you the care of the Church. And that, in effect, is all there was on that day in New York when the REC was founded – a bishop, surrounded by his clergy and faithful laity.

And, to encourage you, John, the care that the bishop shows for his clergy and people is to be reciprocated. Ignatius wrote to the Church at Tralles: ‘It is the duty of everyone, and most especially of the clergy, to see that the bishop enjoys peace of mind’. I think we need to stress that a bit more!

The sheep should care for the shepherd as he cares for them.

- Work with your brother bishops

Whenever he writes to a church, Ignatius is careful to greet its bishop – Onesimus of Ephesus, Damas of Magnesia (apparently a young man), Polybius of Tralles, Polycarp of Smyrna. Each of them is responsible for the portion of the Catholic Church entrusted to them – and together they bear a corporate responsibility for the church as a whole.

We get a glimpse of Polycarp exercising this ministry eirenically in the account of his visit to Anicetus, bishop of Rome:

And when the blessed Polycarp was at Rome in the time of Anicetus, and they disagreed a little about certain other things, they immediately made peace with one another, not caring to quarrel over this matter. … and Anicetus conceded the administration of the eucharist in the church to Polycarp, manifestly as a mark of respect.[2]

John, we are not yet at a stage where the Pope will invite you to preside at the Eucharist in St Peter’s, but the incident is a reminder of a unity that we have lost, and a challenge to work for its restoration.

It’s a challenge that belongs particularly to bishops. Later, in the mid 3rd century, Cyprian of Carthage famously wrote, “The Church forms one single whole: it is neither rent nor broken apart but is everywhere linked and bonded tightly together by the glue of the bishops sticking firmly to each other” (Ep. 66.8.3).

That is exactly what Cummins meant by requiring each Reformed Episcopal bishop to be a bond of unity – binding our churches into a holy unity in Christ.

Your brother Reformed Episcopal bishops here will work with others for the rebuilding of the Church of God here in North America. Your calling, John, is to work with your fellow Reformed Episcopal bishops outside North America to do exactly the same. Cuba, of course, has its own challenges. And so does Europe. We are blessed by the fact that your own European origins are so close that you are really one of us.

The late Presiding Bishop Roy Grote had a vision of a Reformed Episcopal Province in Europe. It may be part of your ministry to help bring that about. Certainly, from its very foundation, the Reformed Episcopal Church has had a burden to take the Gospel overseas, as the presentation of the work of the Board of Foreign Missions at the last General Council reminded us. And, since the 1870s the Reformed Episcopal Church has had a particular concern for the Mother Country of the worldwide Anglican family. After Canada, the United Kingdom was the next country to have a Reformed Episcopal Church established in 1878. And we are still here! Germany and Croatia have obviously followed.

So work with your brother bishops in their various contexts.

- Take the long view.

At the end of his life, when brought before the Roman officials, Polycarp was offered a means of escape: ‘Curse Christ and live’. He replied,‘Eighty and six years I have served him and he has done me no wrong, how then can I blaspheme my king who saved me?’

John, you probably haven’t got another 86 years, but, like Ignatius and Polycarp, you could have an episcopal ministry of several decades. Ask yourself what in ten/twenty years’ time you will wish you had achieved, then start to work towards it now.

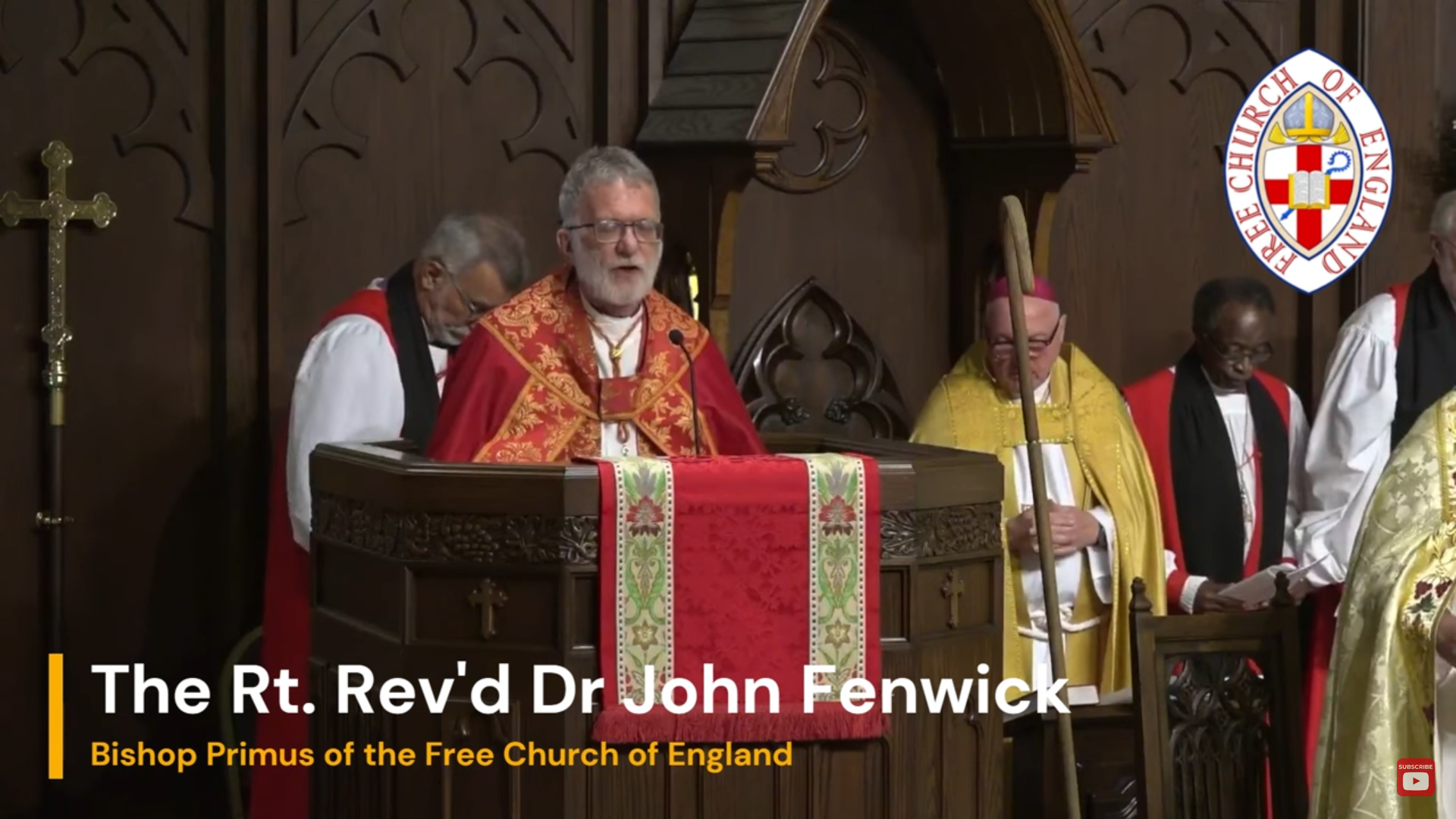

And think of your successors. I am the 13th Bishop Primus of the Free Church of England in a succession stretching back to 1863. Many of our structures and trusts were put in place by the seventh Bishop Primus, Frank Vaughan (consecrated in the REC/UK) in the early 1940s. And many a time in meetings I have silently thanked God for Bishop Vaughan’s wisdom and foresight in putting in place many of the structures that support our mission today. You will be the second Missionary Bishop for Cuba. What do you need to be doing that the 7th Bishop will bless your memory for in many years’ time?

- Be prepared for martyrdom.

Both Ignatius and Polycarp were put to death for their faith. For many of our brothers and sisters in Christ, martyrdom is an all too present reality today. And we in the West must not think ourselves immune. The de-Christianisation of the societies in which we live is progressing fast and it will have consequences for our safety as Christians. My brother bishops, preparing our people for that is part of our ministry today.

There’s a famous quote from Cardinal Francis George of Chicago: ‘I expect to die in bed, my successor will die in prison and his successor will die a martyr in the public square.’

And, John, even if you are not called to die for Christ, you will discover that the ministry of a bishop is a lifelong martyrdom. It’s a martyrdom in two senses. Firstly, in the original meaning of the word, it’s a life of witness – you will be watched, scrutinised – and you will be expected to get it right all the time – to say the right things, make the right judgements. And when you don’t, people will let you know!

But the ministry of a bishop is a martyrdom in the sense that it is a life of continual challenge. St Paul listed stonings, beatings, shipwrecks and sleepless nights among the things he had suffered (2 Corinthians 6:5). I have so far been spared the stonings, beatings and shipwrecks, but I can certainly identify with the sleepless nights! And, says St Paul, ‘apart from other things, there is the daily pressure on me of my anxiety for all the churches’ (2 Corinthians 11:28). Your dispersed flock will bring with them a whole range of challenges. Yes, there are some nice aspects to being a bishop – you get a bit of extra kit, but, don’t expect it to be easy all the way. It wasn’t for Polycarp and Ignatius. And it won’t be for you.

- Don’t lose heart!

In 2 Corinthians 3, St Paul writes that ‘our sufficiency is from God, who has made us competent to be ministers of a new covenant’. He then goes on, ‘Therefore, having this ministry by the mercy of God, we do not lose heart’ (2 Corinthians 4:1).

If this was a secular job we would all have walked away from it long ago. But it isn’t. As long as we see it as something we have by the mercy of God, and look to him to make us ‘competent’, then it becomes do-able and even at times joyful.

Cardinal George, whom I quoted earlier, used to get frustrated that people only quoted part of what he said. The whole quotation is actually this:

‘I expect to die in bed, my successor will die in prison and his successor will die a martyr in the public square. His successor will pick up the shards of a ruined society and slowly help rebuild civilization, as the church has done so often in human history.’

Beyond death comes resurrection.

In our own Anglican story Archbishop Cranmer died – literally ‘in the public square’ in Oxford – having seen all his life’s work completely undone. And yet, three years after his death, the liturgies that he had drafted were in use throughout the parishes of England, and, eventually, across the world. We are using one of them now.

Like Cranmer, not all of us get to see the fruit of our labours. This coming June sees the 80th anniversary of the D Day Normandy landings. Many of the US and other soldiers who fought on that day did not live to see the liberation of Europe. But Europe was liberated.

We here tonight are engaged in a struggle for the liberation of the Anglican heritage, here in North America and beyond. It’s a weary struggle, with many complications. And time and again we need to hear the comforting words of St Paul at the conclusion of his great passage on the resurrection in 1 Corinthians 15:

Therefore, my beloved brothers, be steadfast, immovable, always abounding in the work of the Lord, knowing that in the Lord your labour is not in vain (1 Corinthians 15:58).

You may not see the fruits but in the Lord your labour is not in vain. ‘Therefore, having this ministry by the mercy of God, we do not lose heart’.

Conclusion

So, across the centuries the example and teaching of Polycarp and Ignatius speak to us.

But this isn’t just an exercise in romantic antiquarianism – how nice it would be if we could pretend to be early second century bishops. Cummins appealed to the episcopacy of Polycarp and Ignatius because it is ‘admirably fitted to promote the well-being of the whole visible Church of Christ’. It wasn’t just ancient – it was useful; it was good in itself.

In Cummins’ mind part of its appeal was that it was a system uncluttered by cathedrals, archdeacons and the whole Anglican apparatus.

It was a primitive episcopacy, episcopacy stripped to its essentials, without a lot of baggage, flexible, capable of adapting to a whole new set of opportunities and challenges. Exactly the kind of episcopacy for a missionary bishop in the third decade of the 21st century.

Sit at the feet of the Apostles, stand up against false teaching, be a centre of unity, work with your brother bishops, take the long view, be prepared for martyrdom, do not lose heart.

On 2nd December 1873, at the meeting at which the Reformed Episcopal Church was inaugurated, the odds were that what Cummins was doing would be in vain. Humanly speaking the odds were stacked against it. There was huge opposition. The likelihood of a movement consisting of one bishop, six presbyters and 19 laity surviving was infinitesimally small.

Yet, 150 years later, here we are. We have made our mistakes, but God in his mercy has preserved us and is in these days blessing us with new life and growth. And your consecration, John, is a visible sign of that.

On that day in 1873 Cummins said, ‘ If the work we inaugurate today be of men, may it come to naught. If it be of God, may He grant us more abundantly the Holy Ghost and wisdom to make us “valiant for the truth,” strong to labor and faithful in every duty, and “rejoicing to be counted worthy to suffer shame for His name’.

Those qualities – ‘valiant for truth’, ‘strong to labour’, ‘faithful’ and being prepared to suffer – apply, of course, to Cummins himself. But, as we have seen, they apply also to Polycarp and Ignatius, the models to whom we Reformed Episcopal bishops are to aspire.

This is the episcopacy to which we adhere.

[1] Stott, Authentic Christianity, p.282.

[2] Eusebius, HE, 5.24.